|

| Click to Enlarge

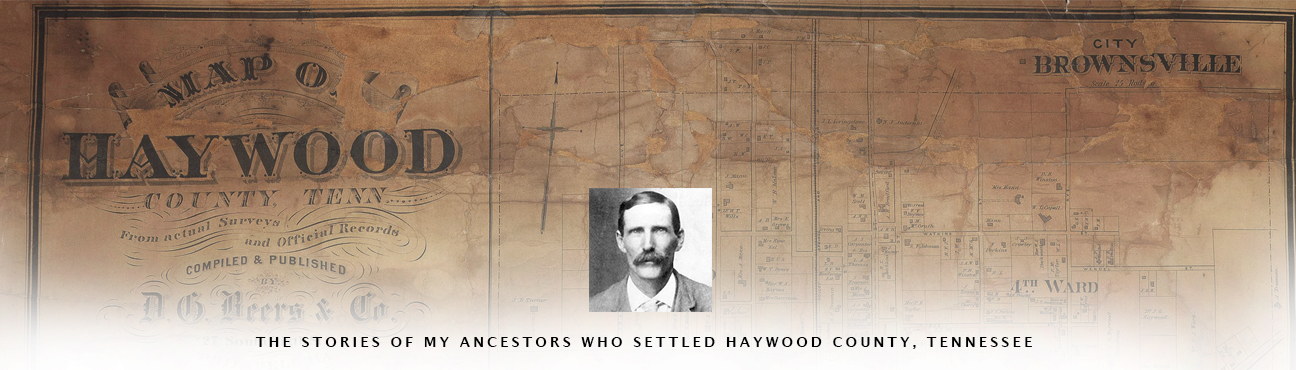

John Wayne as Colonel James Smith |

In school, the role of Indians was always part of our early Tennessee History curriculum and most Memphis-area youngsters growing up in the ’60s and ’70s could count on at least one field trip to Chucalissa Indian Village. It’s not even all that unusual to stumble across flint arrowheads in the area, although I’ve never been that fortunate. While playing in the woods as a young boy, I frequently entertained the idea that an Indian possibly walked over the very spot on which I was standing.

|

| Click to Enlarge

Title page of Colonel James Smith’s book. |

In 1755, when he was 18 years old, Smith was part of an army of 1,400 who were sent to attack the French army at Fort Duquesne (now known as Pittsburg) as part of General Edward Braddock’s British Regiment. In his book, Smith claims he was taken captive by a band of Lenape Indians and stayed with them nearly five years.

“The old chief, holding me by the hand, made a long speech, very loud, and when he had done he handed me to three squaws, who led me by the hand down the bank into the river until the water was up to our middle. The squaws then made signs to me to plunge myself into the water, but I did not understand them. I thought that the result of the council was that I should be drowned, and that these young ladies were to be the executioners. They all laid violent hold of me, and I for some time opposed them with all my might, which occasioned loud laughter by the multitude that were on the bank of the river. At length one of the squaws made out to speak a little English (for I believe they began to be afraid of me) and said, ‘No hurt you.’ On this I gave myself up to their ladyships, who were as good as their word; for though they plunged me under water and washed and rubbed me severely, yet I could not say they hurt me much.”

After his nearly five years living with the Indians, Smith escaped to Montreal where he was captured by the French and held for four months until being traded in a prisoner exchange with the British. Upon his return home, he said his friends and family “found him quite like an Indian in his walk and bearing.”

The film “Allegheny Uprising” was loosely based on Smith and the Black Boys Rebellion and stared John Wayne as Smith.