Is a significant figure from one of the most horrifying battles of the Civil War buried off Poplar Corner Road in Haywood County, Tenn.?

Source: Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs, Library of Congress

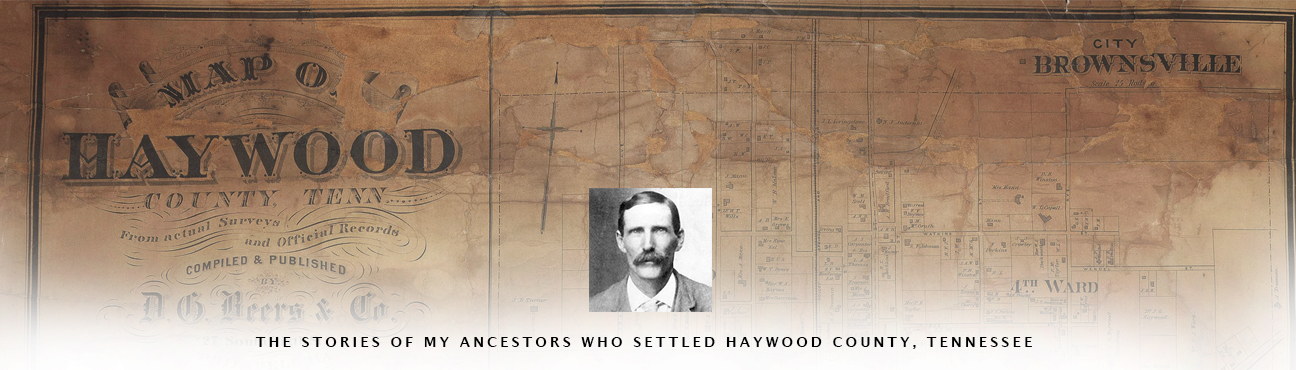

Rodney Wright, a long-time friend of my family in Haywood County, recently emailed regarding a mystery he stumbled upon. It took place in the same area where Richard Nixon originally settled in Haywood County and where both Rodney’s family and mine have lived for generations.

As I blogged a while back, Rodney’s father, Billy Wright, recently helped me figure out the location of Haywood County settler Richard Nixon’s original homestead on Nixon’s Creek.

Like me, Rodney is a history buff and, while researching the Civil War online, he ran across an account of the killing of a Union soldier that sounded familiar in a number of ways to a story his father had shared with him in the past.

According to the story that’s been passed down through the years, a group of Confederate soldiers were camping on a hill near what had been Richard Nixon’s homestead off Poplar Corner Road. With them were Union prisoners of war and, when one tried to escape, he was shot, killed and buried there.

Source: Public domain

The article Rodney came across that sounded familiar to the story was about Major William Frederick Bradford (Sept. 13, 1827 – Apr. 14, 1864), a Union commander who was captured during the famed Battle of Fort Pillow and later shot and killed “near Brownsville” and, in some accounts, buried in an “unmarked grave.”

Rodney decided to see if it was possible Bradford could have been that same solder killed and buried near Nixon’s Creek.

William Frederick Bradford was born in 1827 in Bedford County, Tenn. After graduating from college, he opened a law practice in Troy, Tenn., which oddly enough is only miles away from my new home and where I sit writing this today.

When Tennessee succeeded from the Union on June 8, 1861, Bradford and others who were not in favor of succession, formed the Thirteenth Tennessee Calvary. During the Civil War, more than 32,000 Tennesseans fought for the Union.

An 1986 article in the Tennessee Historical Quarterlyabout The Tennessee Thirteenth Calvary explains why they were so reviled by the Confederates:

In a general sense, they and other Unionists in Tennessee, were considered to be traitors to the South and to their own state…Union men, particularly those who joined Federal regiments, were scorned by Confederate sympathizers during the war, and later by some Southern historians, categorized as renegades, Tories, home-made Yankees and, of course, traitors. p. 136

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

At Fort Pillow, Major Bradford served under Major Lionel F. Booth who commanded the Second U.S. Colored Light Artillery and the Sixth U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery.

The infamous attack on the Fort, led by Nathan Bedford Forest, happened on April 12, 1864. After the death of Major Booth, Major Bradford found himself in charge of the losing end of what has come to be considered by historians as a massacre. Once the Union army surrendered, around 300 black soldiers who had been taken as prisoners of war were murdered, many of them shot point blank in the head.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

The Confederate soldiers’ actions angered the Union leaders to such a degree, they refused to participate in prisoner exchanges and “Remember Fort Pillow” became a rallying cry for black soldiers for the rest of the war.

Major Bradford would meet a similar fate.

He was initially captured while wading in the Mississippi River attempting to escape. After several other attempts at getting away while he was a prisoner, Bradford was eventually held in the jail in Brownsville in Haywood County. After a night in jail, Bradford was to be escorted to Jackson, Tenn. along with other prisoners of war.

The rest of the story is unproven and was disputed at the time by those on both sides of the war. Author Harry Turtledove researched a variety of possible scenarios for his novel inspired by the battle, “Fort Pillow,” and wrote an account of what he determined to be the likeliest scenario.

One of those escorting the prisoners was Jack Jenkins, a Confederate corporal with the Second Tennessee Cavalry from whom Bradford had allegedly escaped in the past. Once far enough outside the town of Brownsville, Jenkins seized upon the opportunity and shot and killed Bradford who was then buried there where he was killed. According to Turtledove, Bradford’s last words were, “shot while trying to escape.”

The article in the Tennessee Historical Quarterly about the Thirteenth includes this reference to Bradford’s death:

Bradford was murdered by his captors a few days after the battle while being escorted as a prisoner on the road from Brownsville to Jackson. It was reported that he was taken captive when the fort fell, but escaped by violating his parole. He was recaptured and later shot under rather controversial circumstances. P 142-143

Is Bradford the Union soldier said to be buried near Nixon’s Creek in the story passed down through generations?

Rodney’s online search turned up a listing on Find a Grave that stated William F. Bradford was buried in the Nashville National Cemetery in Davidson County, Tenn.

A quick call to that cemetery and a conversation with a staff member resulted in the discovery that the Nashville National Cemetery did not actually have William Bradford listed as being buried there. After a review by a volunteer at Find a Grave initiated by Rodney, Bradford’s status was changed to “Lost at War, Specifically: Cemetery Name Unmarked Grave.”

Is Major William F. Bradford the Union soldier said to be buried close to Nixon’s Creek on Poplar Corner Road? Without further evidence, we’ll never know for certain. But the thrill of potentially finding more clues is what keeps those of us like Rodney and me trying to uncover as much forgotten regional history as we can.

You can find more about family lines at HaywoodCountyLine.com or read more blog posts about the history of West Tennessee on my blog page.

Sources:

Fort Pillow Massacre, History.com

Fort Pillow Massacre, Britannica

FindaGrave.com

The Civil War massacre that left nearly 200 black soldiers murdered

Harry Turtledove Wiki

Battle of Fort Pillow and Union Roster

Lufkin, Charles L. “Not Heard From Since April 12, 1864:” The Thirteenth Tennessee Cavalry, U.S.A.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 45, no. 2 (1986): 133-51. Link