|

| Photo/Lib. of Congress

Click to Enlarge

Modern handwritten note in case: Slave nanny/white

child image came from an estate sale somewhere

in the flat lands delta area of Arkansas. |

Slavery as a concept sucks. No one really disputes that now. But it’s hard to get past slavery as a concept and really feel the horror that it truly was.

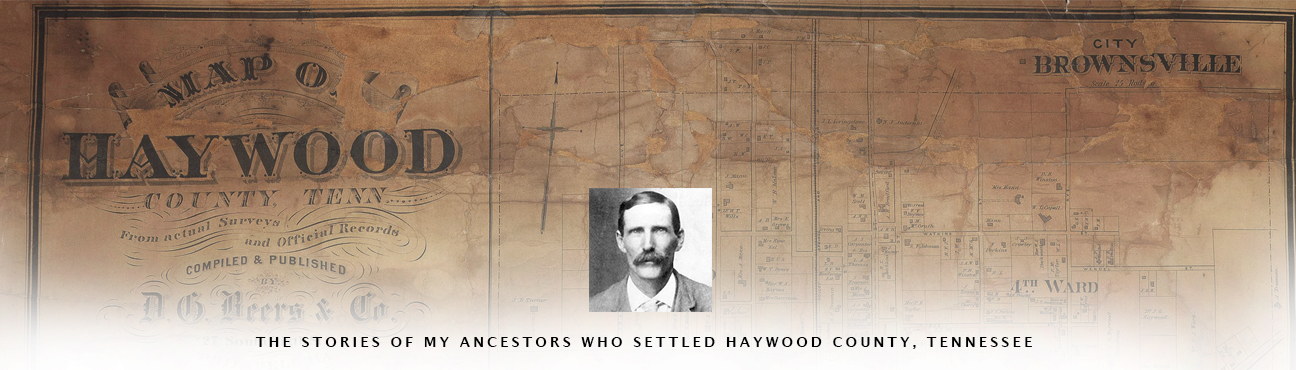

My ancestors who migrated from Bertie County, North Carolina to Haywood County, Tennessee in the 1830s succeeded because the Delta ended up being the perfect place for growing cotton. The more cotton they grew, the more successful they became and the more land they could acquire. And the only way they could grow that much cotton was by using slave labor.

I’ve been reading a lot lately about attitudes and the cultural aspects of slavery in the South in an attempt to figure out was going on in the minds of my slave-owning ancestors in the early 1800s but it hasn’t really connected personally for me until this week when I began reading some of the probate documents from the estate of my fourth great-grandfather, Brother George Williams (1797 – Oct. 3, 1852).

|

| Click to Enlarge

Probate record from the estate of

George Williams, December

term of the Madison County Court

of 1852 |

From the records, I know that when he died, Williams was the owner of four slaves: Milly, a woman who was young enough to be the mother of small children; Ned, Millie’s son who was around three years old; Winnie, Millie’s daughter who was around nineteen months old; and Henrietta, a young girl who was fifteen years old.

|

| Click to Enlarge

Probate Record of the estate of

George Williams, Jan. 5, 1853 |

It seems after George died, the assets of his estate were being divided among his wife Nancy (who remarried quickly after his death), his son Solomon Williams and his grandson Hugh A. Montgomery.

It was determined the four slaves were to be sold and the proceeds split between the family members.

The slaves were “offered at the courthouse door in Jackson, Tennessee on Jan. 1, 1853. Henrietta was sold to Anderson Delapp for $759 while the little children, Ned and Whinney, were sold to Peyton Graves. Interesting to note the family had specifically requested the two children be sold together. That begs the question, if they were empathetic enough to make that request, why not give the children their freedom?

Milly, the children’s mother, was not there to see them sold and taken away. Included in one of the documents was the simple statement “the fourth one Milly having died since the last court.”

|

| Click to Enlarge

Physical and mental evaluation of Henrietta |

One document in particular provides the most insight into the minds of those for whom slavery was a normal part of society. I warn you, it’s not easy to read.

Jackson

January 4, 1853

Mr. Stephens

Dr. Fenner and myself have examined the girl Henrietta belonging to the Williams Estate and as to the state of mind think her about a smart and sensible as she looks to be just the plain ordinary amount of intellect of a coarse field hand. No reasonable ground of objection on this score.

As to the health of body she is in one important particular (of the state of her monthly periods) unsound and from the statement of the negro confirmed by statement of Mrs. Williams has been so since the spring of 1852.

We do not apprehend that she is incurably so but it will require exemption from exposure and skillful medical treatment to give her the best chances for relief from the suppression of the important function and if not relieved (for this often obstinate) her value as a breeding woman would be destroyed and her general health after some time might be so undermined as to lessen decidedly her usefulness as a working hand.

Respectfully submitted by A. Jackson

The sale of all three slaves was later “set aside” and it was determined that they would be sold “as such time as petitioners shall instruct the court.”

This is a story with details I’ll never be able to figure out and it generates a lot of questions that will never be answered.

After the Civil War, many slaves took on the names of their owners so it’s just possible the siblings Ned and Whinney took the last name Williams. Ned Williams would have been born in Madison County, Tennessee in 1848 and Whinney Williams would have been born around 1850. Their mother’s name was Milly.

I’ll never understand how anyone could justify or explain the atrocities of slavery, but by writing about these four, at least I’ll make certain their sacrifice is remembered somewhere.