After reading a few weeks ago that the Brownsville, Tennessee train depot was used as one of the locations for filming the movie “The Liberation of L.B. Jones,” I was anxious to see if it included other locations as well.

Having never heard of the movie, the book on which it was based or the author, I discovered so much I wanted to share, I’m breaking this blog entry into two parts.

Although I was really only looking for interesting shots that would show what the West Tennessee area looked like, what I actually discovered is a story of racial injustice that took place both both in literature and in real life.

As I hoped, the film does offer a really good look at the train station and some of the region as it appeared in 1969 when the movie was filmed. Those familiar with the area will notice the town square scenes were filmed in Trenton, Tennessee. I pulled out a few of the clips and uploaded them to YouTube so you can check them out for yourself.

Be sure to turn up your volume so you hear the funky score which was done by film composer Elmer Bernstein.

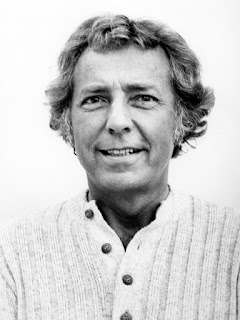

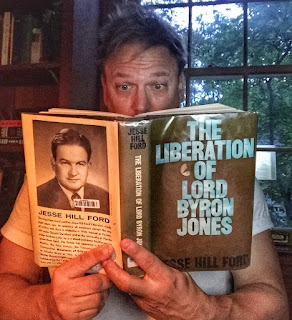

The film was based on “The Liberation of Lord Byron Jones,” a novel by Southern author Jesse Hill Ford (1928 – 1996).

I finally finished the book this morning. If, like me, you aren’t a fan of the “n” word, racism, bullies, brutality and cruelty, you’ll have a difficult time getting through the book.

As one reviewer put it, the book features, “an astute study of the social stratification and power imbalance in a southern town in the early sixties.”(1)

Ford grew up in Nashville and attended college at Vanderbilt and The University of Florida, studying under the fugitive writers Andrew Lytle and Donald Davidson.

While he was a student at Vanderbilt, Ford began working for the Nashville Tennessean and became friends with another reporter, John Seigenthaler, who I actually had the pleasure of meeting. Before his death in 2014, he was a passionate supporter of the Newseum and a tireless champion of the First Amendment. In an interview for a 1997 article for Esquire, Seigenthaler said, “Jesse was a very intense young man who took himself more seriously than most people do in a newsroom. He was very conscious even then of what he wanted to be.” (2)

After a stint in the Navy during the Korean War and a short career in PR, at the age of twenty-eight, Ford decided to focus on writing a novel. He and his wife, Sally, moved to her hometown of Humboldt so he could write full time.

He sold a short story to Atlantic Monthly and wrote a play, “The Conversion of Buster Drumwright,” which aired on CBS in 1960. With a title inspired by Indian mounds located near Humboldt, his first novel, Mountains of Gilead, was published in 1961.

He sold a short story to Atlantic Monthly and wrote a play, “The Conversion of Buster Drumwright,” which aired on CBS in 1960. With a title inspired by Indian mounds located near Humboldt, his first novel, Mountains of Gilead, was published in 1961.

Photo/Jesse Hill Ford Documentary

Photo/Jesse Hill Ford Documentary

Jesse Hill Ford

His writer’s imagination was then inspired when he began hearing about the 1955 murder of James Claybrook, a successful black undertaker from Humboldt. The undertaker was found shot twice in the chest and propped up against a tree on a deserted country road, right outside town. Ford’s maid speculated with others in the community that the undertaker’s pregnant wife, Dorothy, had been having an affair with a white policeman, which led to his murder.

The novel Ford wrote based on those actual events was set in fictional Summerton, Tennessee, and was about a wealthy black undertaker who insists on divorcing his much-younger wife, because she was having an affair with a white policeman. The divorce would expose the (then illegal) biracial affair in court, and the undertaker’s refusal to back down leads to his brutal murder by the policeman.

Photo/Jesse Hill Ford Documentary

Photo/Jesse Hill Ford Documentary

Jesse Hill Ford

Racially charged at a time when the hard-won civil rights laws of the 1960s were being tested and integration was just beginning, the novel was a cultural, critical and commercial success for Ford. It was nominated for the National Book Award in 1966 and selected for the Book of the Month Club, exposing it to thousands of readers around the nation. Ford was also awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for fiction writing.

As the New York Times wrote, “Mr. Ford seemed destined to take his place among the pantheon of Southern writers.”(3) He was compared elsewhere to William Faulkner and Flannery O’Conner.

“This is a novel which no American can disown but which only a Southerner could have written. The Liberation of Lord Byron Jones is a realistic narrative of racial crisis, set in a small Southern town that far transcends its local setting. Perhaps only once a decade does a work of fiction so completely enter and embody current conflict…he gives life and breath to the men and women the headlines and television reports of the civil rights revolution have failed to make us understand.”

“The Liberation of Lord Byron James” book jacket

Stirling Silliphant, the Oscar-winning screenwriter for “In the Heat of the Night,” bought the movie rights and Ford began working with him on the script in Los Angeles. With fame and fortune came a lifestyle filled with temptations that Ford apparently found difficult to resist.

William Wyler and Audrey Hepburn

William Wyler and Audrey Hepburn

on the set of “The Children’s Hour” in 1961

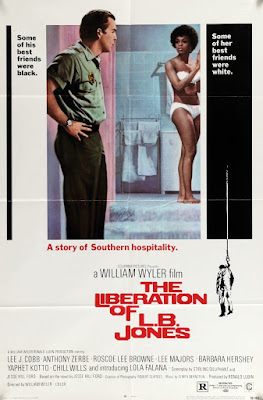

The movie, “The Liberation of L.B. Jones” was directed by legend William Wyler. It starred Roscoe Lee Browne, Barbara Hershey, Lola Falana and the six million dollar man himself, Lee Majors.

This would be the last project for Wyler, whose body of work included “Ben-Hur,” “The Best Years of Our Lives,” “Roman Holiday,” “How to Steal a Million,” “The Children’s Hour” and “Funny Girl.”

William Wyler: The Authorized Biography by Axel Madsen, gives a little insight into the filming in West Tennessee:

“In February of 1969, Wyler went to Tennessee to scout locations and to meet Ford in his hometown of Humboldt, eighty miles northeast of Memphis…Tennessee was another world, flat cotton country with acreage set aside for raising strawberries or feeding Black Angus and Hereford cattle.

Driving up to Humboldt, he first saw the quarry ponds where they cut rocks for buildings, then the swamp where cypresses rose from dark stained waters. South of town, were the Indian mounds known as the Mountains of Gilead, which had been the title of Ford’s first novel. On the city limits were the cemeteries—one for white folks and one for blacks.

Spending over $200,000 in Humboldt and the environs, the company filmed in half a dozen small towns—Humboldt, Trenton, Gibson and Brownsville, and all eighty-odd members of the cast and crew stayed at the Holiday Inn.” (4)

Unlike the novel, the film was neither a financial nor critical success. What worked in a novel, didn’t translate well to the movie theater.

“I’m sure that Wyler and his screenwriters, Stirling Silliphant (who adapted “In the Heat of the Night”) and Jesse Ford Hill, were out to make a suspense movie that would also work as contemporary social commentary. In the interests of melodrama, they have simplified the characters from Hill’s novel to such a degree that they seem more stereotyped than may have been absolutely necessary—a problem that is aggravated by some of the casting.” The New York Times

“This story of a glossed-over Negro’s murder by a Dixie policeman is, unfortunately, not much more than an interracial sexploitation film.” Variety

“The cast gives some strong performances, ultimately the film is an empty affair. The questions of racism and southern prejudice had been well handled by other films long before this. Had it been made 10 years earlier it would have been a landmark, but in 1970 it was no longer fresh material.” TV Guide

The negative publicity and tone of the film brought even more notoriety to Humboldt, angering both whites and blacks in the community. By this time, the Ford family was living at Canterfield, a large home in Humboldt built by Ford. They began receiving death threats, obscene phone calls and other forms of harassment including garbage dumped on their massive lawn.

When the Humboldt black and white high schools were integrated by court order in 1970, the white players maintained their starting positions, which of course, angered much of the black community. Ford’s son, Charlie, was a starting running back and was shocked one morning at school to find “Kill Charlie Ford” carved into his desk.

Always a bit paranoid, Ford’s anxiety continued to increase with each threat.

Photo/Jesse Hill Ford Documentary

Ford’s life would soon take a turn that would be considered too ironic if it were written in a novel. The writer, who made his fame and fortune writing about crimes against black people, would soon end up murdering a black man himself.

(1) Christa Buschendorf, Astrid Franke and Johannes Voelz, eds., Civilizing and Decivilizing Processes (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011), 230.

(2) John Taylor, “The Liberation of Jesse Hill Ford,” Esquire, February, 1997, 74.

(3) Robert McG. Thomas Jr., “Jesse Hill Ford, 66, a Novelist Who Wrote of Race Relations,” New York Times, June 5, 1996.

(4) Axel Madsen, William Wyler: The Authorized Biography (Open Road Distribution, 2015), 100 – 112.

For more blog entries, visit my Blog Home Page or to check out the genealogy research about my specific family lines, go to my Haywood County Line Genealogy Website.