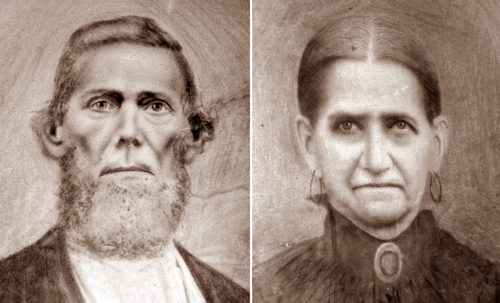

My 3rd great-grandparents Thomas A. and Amelia Dyson Lovelace

My 3rd great-grandparents Thomas A. and Amelia Dyson Lovelace

Our Mutual Lovelace Ancestry

My 3rd great-grandfather Thomas A. Lovelace (1812-1876) was born in Iredell County, North Carolina to Thomas and Amelia Dyson Lovelace. His older brother, Levi Lovelace (1804-1871), was eight years old when Thomas was born. It was a large, prosperous family and, when their father died in 1829, he left each of them “the plantations on which they lived and suits of strong cloth to make them equal to what the others got.” When Thomas left Iredell County, he sold Levi the plantation he had inherited from their father for $500.

By 1855, Thomas had settled in Haywood County, Tennessee after a stay in Kentucky. He married Quincy Angeline Shirley (1828-1898), the daughter of Uriah and Unity Shirley, who had lived in Haywood County for many years. Thomas was the father of Charles Buchanan Lovelace (1858-1938) who was the father of James Luther Lovelace (1885-1968) who was the father of Guy Clinton Lovelace (1916-1997) who was the father of my mother, Shirley Lovelace Williams. These direct descendants from Thomas and Quincy Lovelace to me were born, lived and died in Haywood County and all are buried there in the Zion Baptist Church cemetery. My mother was the first to leave when she moved to Memphis in the late 1950s.

Thomas’ brother Levi eventually migrated to Franklin County, Missouri. He was the father of Thomas Jones Lovelace (1824-1897) who was the father of John L. Lovelace (1860-1943) who was the father of Edgar Blain Lovelace (1881-1971) who was the father of Dr. William “Randy” Lovelace II (1907-1965), who I’m writing about today.

Lieutenant Colonel William Randolph “Randy” Lovelace II

Dr. Randy Lovelace was born Dec. 30, 1907 to Edgar and Jewel Costly Lovelace in Springfield, Missouri. When Randy was six months old, his family moved to New Mexico where they homesteaded 800 acres west of the Pecos. They later moved to Albuquerque.

Randy attended Harvard University where he received a medical degree in 1934. After a surgery fellowship with the Mayo Foundation, he became interested in military and aviation medicine and that passion influenced the rest of his career.

The First Astronauts

Dr. Lovelace had already made an impressive impact on the world of science and aviation by 1958 when he was chosen by NASA to chair a special advisory committee on life sciences that would help decide who would be fit enough to travel into space and back.

Dr. Lovelace was uniquely qualified for that position. In the years between receiving his Harvard medical degree and his chair appointment, he had developed a number of aviation safety devices including a breakthrough high-altitude oxygen mask. He also founded The Lovelace Clinic in Albuquerque where his research and testing of high altitude parachute jumps continued. He received the Distinguished Flying Cross in 1947.

Dr. Lovelace (far left) describing the rigorous testing he designed to select the astronauts at a press conference introducing the Mercury Seven, America’s first astronauts.

Dr. Lovelace (far left) describing the rigorous testing he designed to select the astronauts at a press conference introducing the Mercury Seven, America’s first astronauts.

Working for NASA, Dr. Lovelace used his resources, years of research and personal experience with pilots and aircraft to create the tests that would determine who had “the right stuff” to become an astronaut. On April 9, 1959, those who had responded best to his tests were introduced to the world as The Mercury Seven. Dr. Lovelace’s guidelines were also used to help select astronauts for the Gemini and Apollo programs.

Women in Space

Not all Dr. Lovelace’s ideas were fully embraced by NASA. He believed women would make great astronauts and, in some ways, would be better than men because they were smaller, lighter and consumed less calories.

Although NASA didn’t specifically prevent women from serving in the space program, they did require that astronauts be experienced military jet test pilots. Since this position was only open to men, it effectively shut women out. Although the idea of women astronauts was unpopular at NASA, Dr. Lovelace set out to prove them wrong the way he had solved other challenges he faced throughout his career; with science and research.

In February 1960, Jerrie Cobb became the first woman pilot to be tested at Dr. Lovelace’s private clinic in Albuquerque. The testing was so successful, he announced the results in August 1960 at a conference in Stockholm, Sweden, and Cobb and the cause of women in space became a media sensation.

[ngg_images source=”galleries” container_ids=”1″ display_type=”photocrati-nextgen_basic_thumbnails” override_thumbnail_settings=”0″ thumbnail_width=”240″ thumbnail_height=”160″ thumbnail_crop=”1″ images_per_page=”20″ number_of_columns=”0″ ajax_pagination=”0″ show_all_in_lightbox=”0″ use_imagebrowser_effect=”0″ show_slideshow_link=”1″ slideshow_link_text=”[Show slideshow]” order_by=”sortorder” order_direction=”ASC” returns=”included” maximum_entity_count=”500″]

Dr. Lovelace and others hoped that by proving women could mentally and physically perform the same or better than men, they could convince NASA to change the requirement that only jet test pilots be considered for the program. Dr. Lovelace selected 25 woman to be tested as astronaut candidates. The women had to be healthy, under the age of 35, have at least a bachelors’ degree, hold a second class medical certificate and an FAA commercial pilot rating or better and have over 2,000 hours of flying time. The oldest candidate, Jane Hart, was a forty-one year old mother of eight and the wife of U.S. Senator Philip Hart of Michigan, while the youngest was Wally Funk, a twenty-three year old flight instructor.

Jacqueline Cochran, a famous pilot and businesswoman, joined the project as an adviser and paid all of the women’s living expenses during the tests.

Thirteen women passed the physical examinations that Dr. Lovelace had developed for NASA’s astronaut selection process, and he began referring to them as the First Lady Astronaut Trainees or “FLATs.” Publicly, they became known as the Mercury 13. They were:

- Jerrie Cobb

- Wally Funk

- Irene Leverton

- Myrtle “K” Cagle

- Jane B. Hart

- Gene Nora Stumbough Jessen

- Jerri Sloan Truhill

- Rhea Hurrle Woltman

- Sarah Gorelick Ratley

- Bernice “B” Trimble Steadman

- Jan Dietrich

- Marion Dietrich

- Jean Hixson

The next step on their path to becoming astronauts was for the women to go to the Naval School of Aviation Medicine in Pensacola, Florida for advanced testing using military equipment and jet aircraft. Unfortunately, using the excuse that testing women as potential astronaut candidates distracted public attention from the mission of beating Russia to the moon, NASA refused to endorse the project and the Navy would not allow the use of their facilities for an “unofficial” project.

Photo: Makers

Photo: Makers

A protest in the 1970s at Mount Holyoke College calling for women to be trained as astronauts.

“Let’s Stop this Now!” Lyndon B. Johnson

Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson was also not a fan. At the bottom of a memo about the program, he wrote, “Let’s Stop this Now!” in very large handwriting.

After publicity around the issue, public hearings were convened before a special subcommittee of the House Committee on Science and Astronautics at which some of the women testified. Nothing came from testimony and none of the Mercury 13 would ever be included in the space program.

Image: LIFE Magazine

Image: LIFE Magazine

October 25, 1963 issue of LIFE magazine featuring the Mercury 13 and a Clare Booth Luce editorial “But Some People Never Get the Message.”

The public was reminded again of Dr. Lovelace’s work and the Mercury 13 when Soviet cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman in space in 1963. Clare Booth Luce published an editorial in Life magazine criticizing NASA for keeping women out of the program.

“Why did the Soviet Union launch a woman cosmonaut into space? Failure of American men to give the right answer to this question may yet prove to be their costliest Cold World blunder.” Clare Booth Luce in Life magazine

In 1964, Dr. Lovelace was appointed by President Johnson as Director of Space Medicine for NASA.

The Cumberland News, Cumberland, Maryland, Page 1

The Cumberland News, Cumberland, Maryland, Page 1

Sadly, and with no small amount of irony, Dr. Lovelace’s career was cut short in 1965 when he and his wife were tragically killed when their chartered airplane crashed in the Colorado mountains as they were traveling home to Albuquerque from Aspen. He was posthumously promoted to the rank of Major General in February 1966.

For more information about Dr. Lovelace and his role in women in flight, check out the History Channel documentary, Mercury 13 – The Secret Astronauts.

NASA would not send a woman into space until 1983, when Dr. Sally Ride became the first American woman in space on the shuttle Challenger.

Today, Dr. Lovelace’s legacy continues to grow and The Lovelace Family of Companies, under the umbrella of the parent company Lovelace Respiratory Research Institute, serve to advance public health through research, development and service in biomedical science.

You can find out more about the Lovelace Family on their page of my website, my other family lines at HaywoodCountyLine.com or read more blog posts about the history of West Tennessee on my blog page.

Sources:

International Space Hall of Fame

Lovelace Respiratory Research Center History

On a Comet Always (.pdf)

America’s Forgotten Female Astronauts

A Space of Their Own

Lovelace’s Women in Space Program

Right Stuff, Wrong Gender: The Women Astronauts Grounded by NAS

Mercury 13 – The Secret Astronauts