I just finished Jeanette Keith’s 2012 book “Fever Season: the Story of a Terrifying Epidemic and the People Who Saved a City.” 2018 is the 140th anniversary year of this particular outbreak, so anyone already interested in West Tennessee history will find her book especially captivating.

I just finished Jeanette Keith’s 2012 book “Fever Season: the Story of a Terrifying Epidemic and the People Who Saved a City.” 2018 is the 140th anniversary year of this particular outbreak, so anyone already interested in West Tennessee history will find her book especially captivating.

In the Mississippi River Valley more than 18,000 died of yellow fever in just three months. At the time, Memphis had a population of 50,000, but when it became clear this was going to be an outbreak that should be taken seriously, 30,000 abandoned the city in a panic. Of the 20,000 who remained in the city during the epidemic, more than 17,000 contracted the disease and more than 5,000 of those died.

Anyone who has spent time around the Delta in summer knows the feeling of hearing those dreaded mosquitoes buzzing around your ears. Today, the most we have to fear is a few hours of annoyance as we try to scratch the itch away. However, for many of our ancestors that bite was a death sentence, and they didn’t even know it.

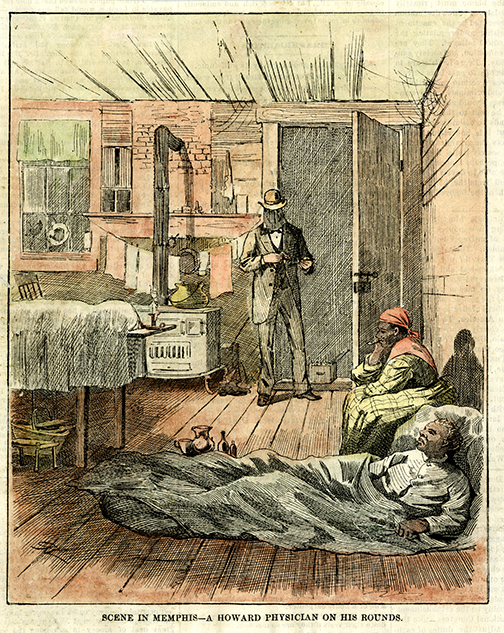

A Howard Physician on His Rounds, Memphis, Tennessee, 1873

Tennessee State Library and Archives Manuscript Collection

And an especially ugly death it was. Not only did patients bleed through their eyes, nose and ears, one of the worst symptoms was bleeding internally which resulted in “black vomit.” Those with yellow fever also suffered from bright yellow skin and eyes, hence the name of the disease.

Yellow fever is spread through the bite of an infected mosquito that has been infected by biting someone who has been infected with the virus. It was a deadly cycle that was compounded in 1878 by an early heat wave and heavy rains that resulted in even more of the deadly insects than usual.

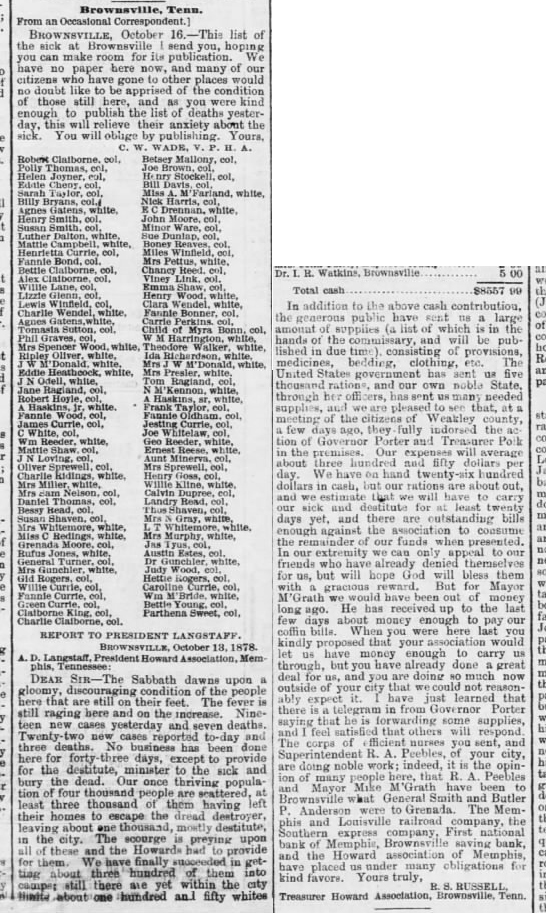

Report from R. S. Russell to President of the Memphis Howard Association on the state of Brownsville, Tennessee during the yellow fever epidemic of 1878. The Howard Association was a volunteer group of young businessmen who organized a medical corps to help the devastated city. Memphis Daily Appeal, Oct. 17, 1878

Some of those who left Memphis early took the fever with them, and towns on the railroad lines suffered nearly as badly as Memphis. Keith writes, “When (Dr. A. D.) Langstaff took the train out to Brownsville, Tennessee, about fifty miles east of Memphis, he found that most of the country doctors had remained at their posts during the epidemic, but many had died. ‘Persons were dying—had died, and had remained unburied…’”

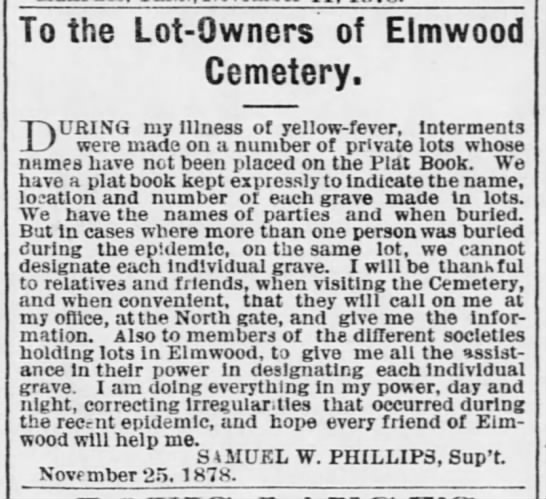

Open letter from the superintendent of Elmwood Cemetery requesting help in identifying the locations of graves of yellow fever victims. Memphis Daily Appeal, Nov. 29, 1878

As the epidemic progressed, the bodies of the dead began to deteriorate in homes, in the streets and even at the cemetery. For more than 15 years, Elmwood Cemetery was included in one of my go-to bike routes. It’s a beautiful, historic cemetery filled with old trees, ornate headstones and reminders of Memphis’ history. Back in 1878, Keith points out that during the outbreak, Elmwood’s serenity disappeared. There were coffins lying all around with only a few men left to dig the graves. Ultimately, many of the dead, no matter how wealthy in life, were buried in a mass grave called “No Man’s Land” with others from all walks of life.

My daughter Alex’s school field trip to Elmwood Cemetery

Speaking of Elmwood Cemetery, no visit is complete without stopping to pay respects at the grave of Annie Cook, the madam who stayed in Memphis and turned her whorehouse into a hospital. After weeks of nursing the sick and dying, she too became ill and died. A hundred years after her death, a philanthropic Memphis couple had a granite stone placed near her grave on which was written, “Annie Cook, Born 1840, Died of Yellow Fever in 1878, A nineteenth century Mary Magdalene who gave her life to save the lives of others.”

I have a personal connection to the memorial honoring the yellow fever martyrs like Annie Cook.

Memorial to those who sacrificed their lives in Memphis to care for the yellow fever victims in 1878.

The park directly in front of my in-laws house on one of the bluffs of the Mississippi River became Martyrs Park on January 3, 1971. The park features a memorial designed by Harris McLean Sorrelle that pays tribute to the sacrifice of all those who died.

A plaque at the memorial reads:

In grateful memory of the sacrifice of the heroes and heroines of Memphis, in the 1870’s, who gave their lives serving the victims of yellow fever. Thousands died and thousands fled during several epidemics. The last one, in 1878, devastated the city, leaving few survivors. The acts of love and courage, far beyond the call of duty, merited the gratitude and admiration of the citizens of Memphis, and of the world, as history revealed the story. “Greater love than this no one has, that one lay down his life for his friends.” John 15:13, January 3, 1971

Keith points out that those who stayed behind or even came to Memphis to help the sick and dying came in every race, religion and sex. “Neither heroism nor villainy could be predicted by public standing, gender or race. Upstanding citizens abandoned their families, and prostitutes and sporting men stepped up to care for the sick. White elected officials deserted their posts, but black militiamen stood fast as guardians of the city.”

“Fever Season” is a fascinating true story of a moment in history when martyrs were made and the fabric of a city was changed forever.

You can purchase a copy of Fever Season on Amazon, find out more about each of my specific family lines at HaywoodCountyLine.com or read more blogs posts about the history of West Tennessee on my blog page.